The dragon Prince

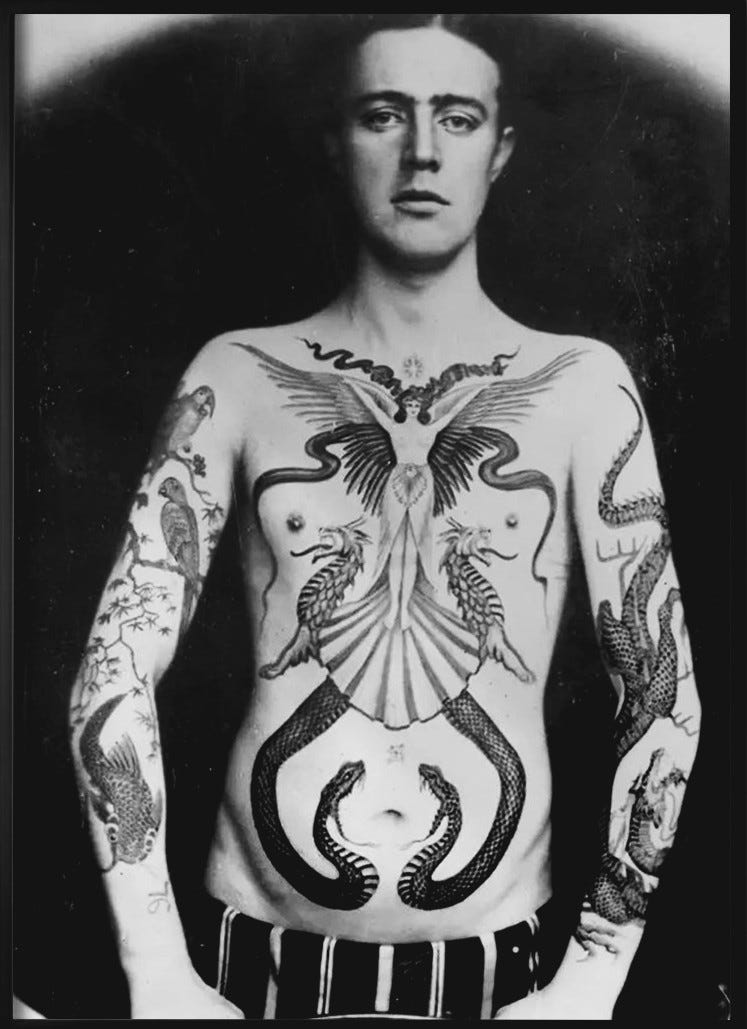

Tokyo, October 1881. A young English prince, George of Wales, waits for his tattooing session. The master tattooist, or horishi, himself fully covered with traditional Japanese motifs, starts working on a “large dragon in blue and red writhing all down the arm” of the prince. He starts by outlining the drawing in Indian ink and water, moving on to pricking the permanent design with “little instruments that look like camel-hair brushes, only instead of hairs they consist of so many very minute needles.”

In his diary, the prince doesn’t name this instrument, the tebori; he also fails to name the horishi—we still don't know, in truth, his identity. Some mention Karakusa Gonta from Asakusa, and others mention Hori Chiyo from Yokohama. These artists’ work, like the work of other artists that bridged the Edo (1603–1868) and Meiji (1868–1912) eras, was recognized worldwide for their detail and overall remarkable craftsmanship.

These artists (or master tattooists, as they consider themselves “crafters”) executed Horimono tattoos, one of the most iconic Japanese traditional tattoo art forms with deep cultural roots but also a turbulent past and an even more troubled future. For starters, the Japanese horishi who worked on the prince of Wales’ arm, whoever he was, was actually only legally allowed to ink foreigners, as the practice had been abolished among the Japanese.

Later, Prince Edward (future Edward VIII) arrived in Japan to follow in his royal relatives' footsteps, but, much to his disappointment, the practice had been outlawed altogether by that point. These tattoos were extremely popular among sailors and wealthy people from the West, which astounded the officials and elites of Japan, who reviled the practice. How was it possible that the Japanese tattoo artists were at the same time so respected for their excellent job while also being part of such a stigmatized practice?

What is Horimono?

Horimono (“carve”/”engrave”, from the verb horu, and “thing”, from mono) is easily recognizable for its traditional motifs and for how it uses the body as a canvas, surrounding the entire torso, arms, and even upper legs with a frame, or gaku, of wind swirl or waves. Being on the prickly side of the tebori is a role of pain and patience, a spiritual journey by itself.

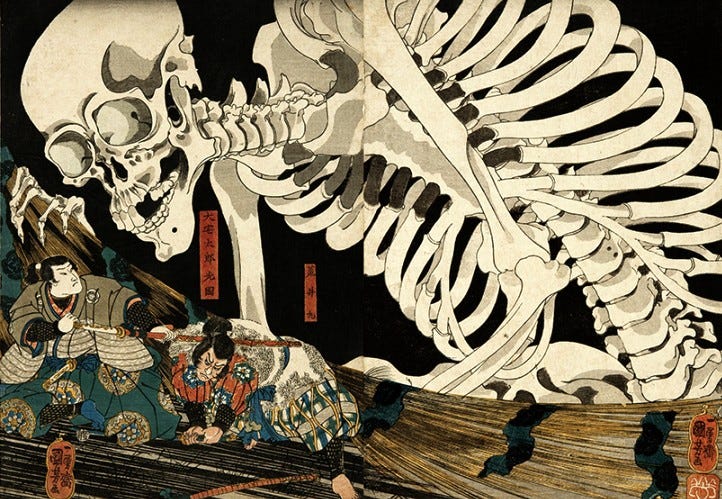

The iconography ranges from traditional symbols, chosen not only for their everlasting themes but also for their spiritual significance as protectors or amulets, to landscapes and human figures inspired by or sharing their inspiration with ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings, including kabuki actors, shunga (erotic) scenes, and yokai (creatures of Japanese folklore).

The horimono tattoo is traditionally executed with the tebori, the needle instrument, by a horishi, a master (shi) “engraver”, a title given after a formal and rigid apprenticeship. The title was also shared by ukiyo-e woodblock printers, which is why, in the Edo period, they tattoists were also known as horimonoshi. Throughout the history of this art, a significant number of tattoo masters are called a combination of “Hori” and another name (usually indicative of their region), and this name combination is passed throughout generations of masters (from master to former

apprentice).

🌺🍵 Special thanks to Catarina Periera who's been a stellar collaborator and a superb Ghostwriter. I'm very proud of the contributions she's made here and I admire the work ethic and grit that she demonstrated during the writing of this Mini-series.

✒️🐉 If you’re looking for exclusive content unpublished here on Substack, be sure to subscribe to my blog on Medium. It’s packed with a variety of pieces from reviews, social commentary, Poetry, health and Wellness, Nutrition , to Fiction Serials. Join the community and stay in the loop—consider subscribing. 🙂⬇️

https://thefictionseries.com/twisted-knight-vol-8-d4fb013a1b42