What is Irezumi?

Horimono is commonly mistaken for Irezumi, and that’s probably related to its modern negative connotations. Horimono traces its lineage from long before the Meiji era but came to be as we know it in the Edo era.

In 1720, during the Edo period, the Japanese ruling class instituted the enforcement of the permanent ink mark on individuals deemed criminals by the authorities. This mark could go from simple lines around the forearm to a kanji on the forehead, making people who committed more serious crimes easily recognizable. This practice was called Irezumi.

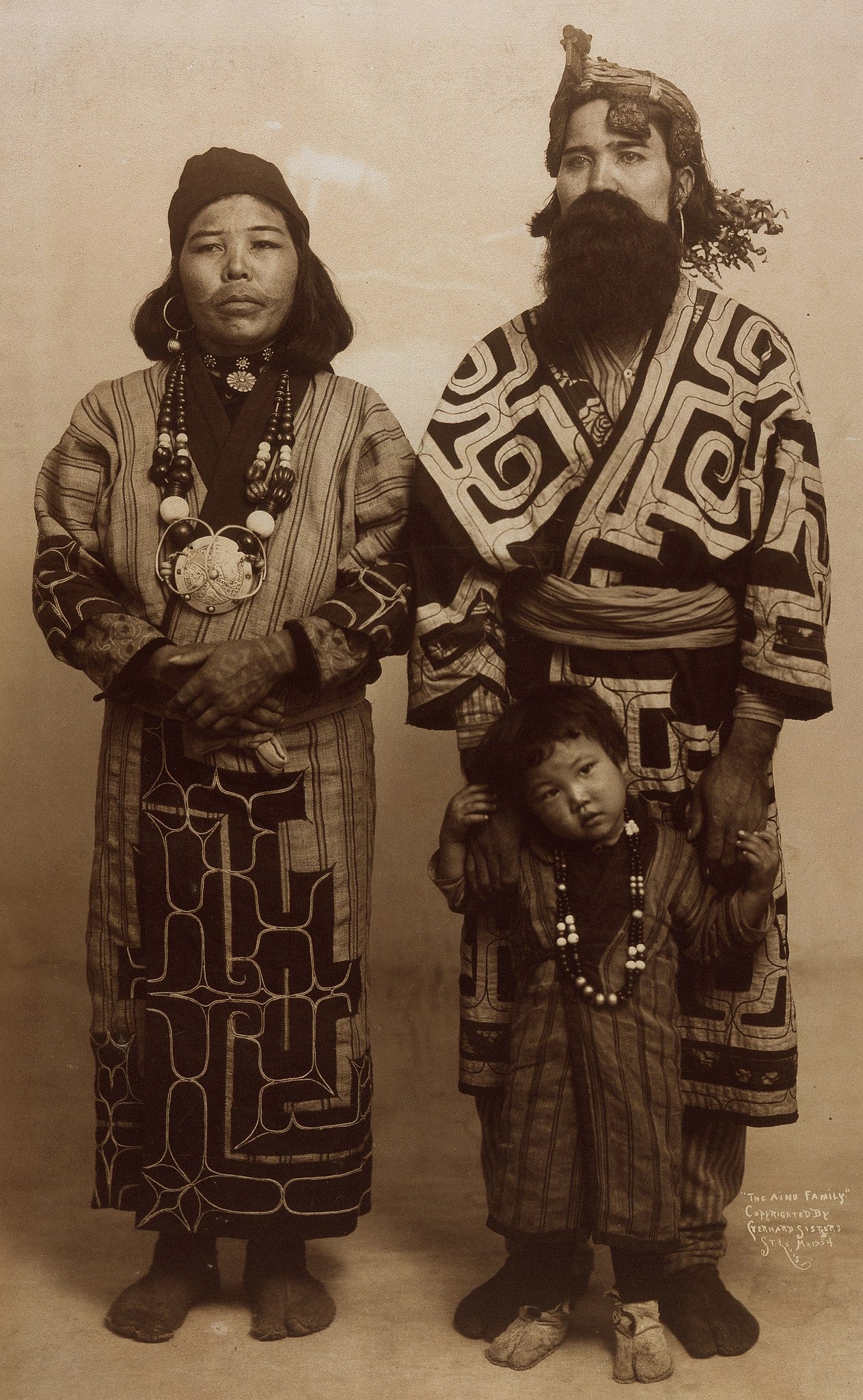

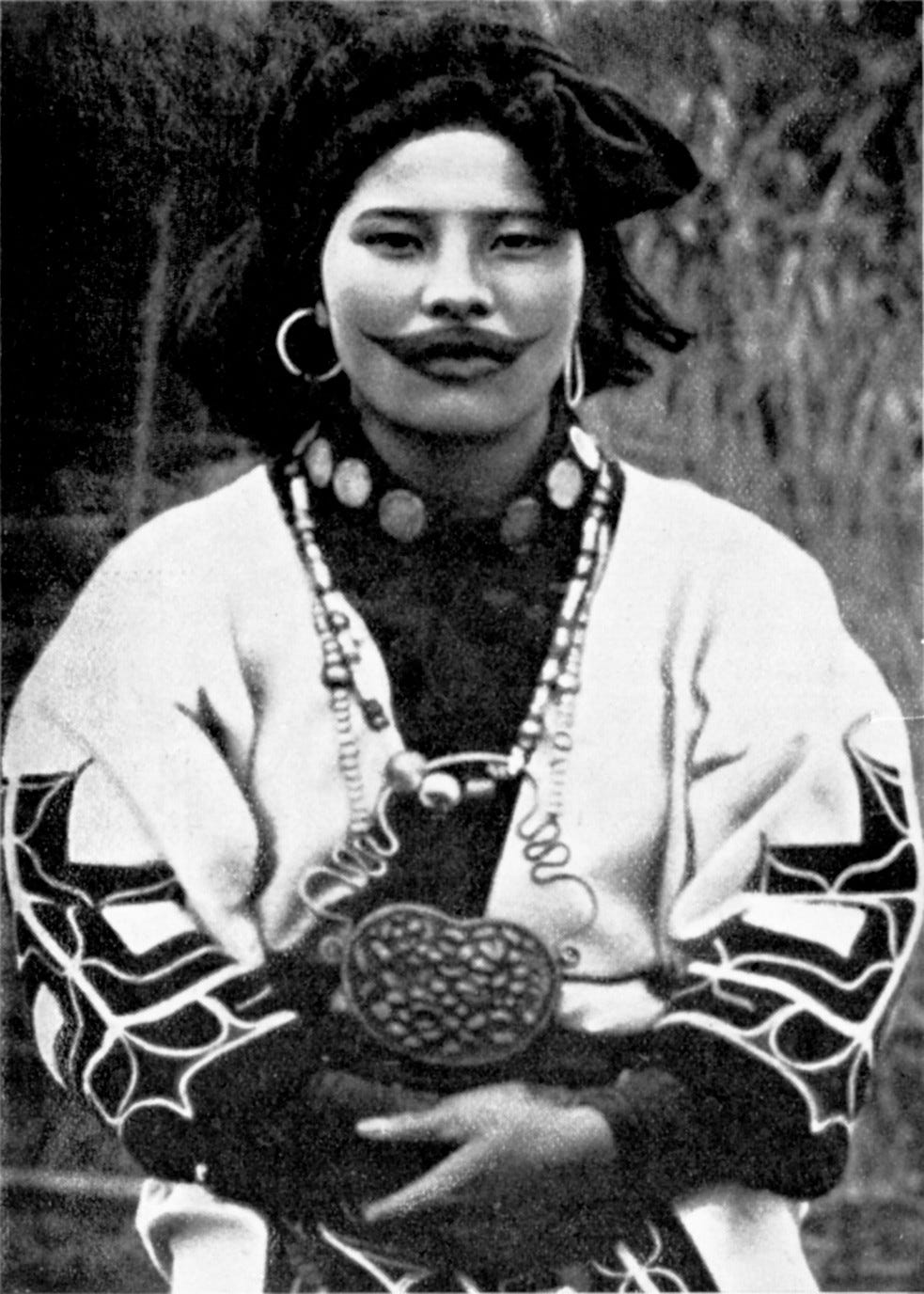

Tattoos were then a sign of the “other.” The lower castes, Hinin and Burakumin, forced to perform impure yet essential societal functions, were too branded with the irezumi marks. Ainu women wore facial tattoos, associating the ink with a discriminated ethnic minority.

Horimono, Suikoden and Ukiyo-e

It’s common to mark the enforcement of the irezumi as the start of the discrimination against tattoos in Japan, and it did contribute significantly to it. But with every push against tattoos from authorities and the samurai class, there was a boost of popularity in other social classes, especially among crafters and other workers, and in alternative social spaces, like the pleasure quarters (to mark a connection between courtesans and clients or for fashion purposes) and the criminal world (even if in part to help cover the shameful irezumi marks). Tattoos were one of the great class signifiers—reviled by the elites, fully embraced by the working class.

The samurai culture stood so tall and far from ordinary people that the commoners were more eager to seek their hero model elsewhere. And they did find it prominently in the Suikoden.

Water Margin, or Outlaws of the Marsh, is a Chinese novel about outlaws fighting a corrupt government. Originally written between the 13th and 16th centuries, translations of the work, commonly known in Japan as Suikoden, exploded in popularity at the start of the 19th century.

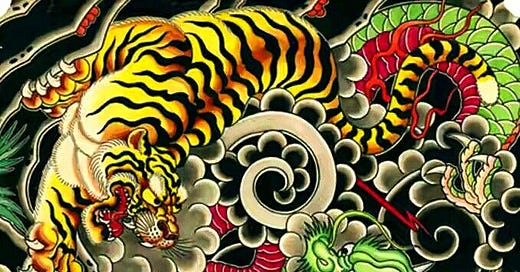

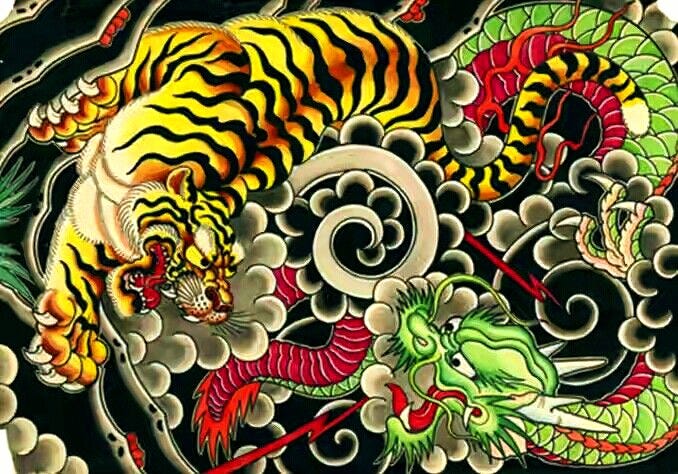

From 1827 to 1830, the master printmaker Utagawa Kuniyoshi produced a series of wood-print engravings that portrayed Suikoden’s heroic characters. The characters were depicted with Chinese cultural markers to evade the accusations of defiance against the rulers. Still, they were almost entirely covered with tattoos that would accentuate these outlaws' heroic status.

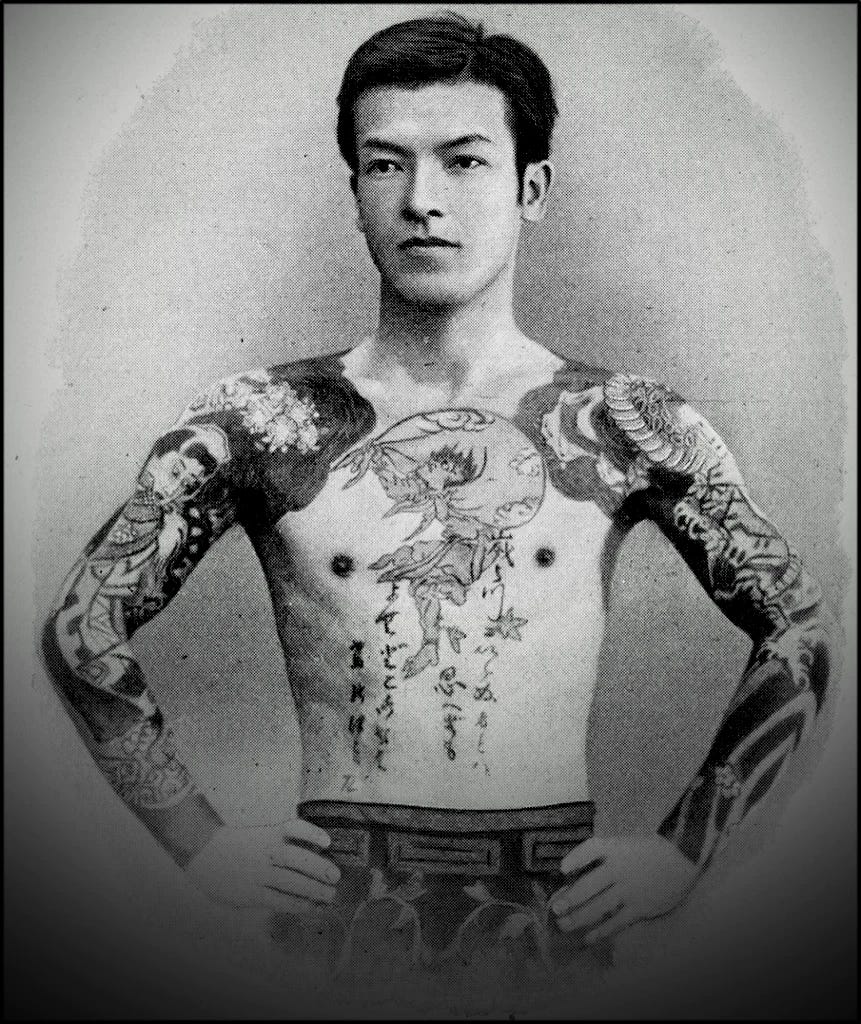

The working class was quick to embrace these characters’ aesthetics, cementing the style of the horimono in deep connection with the style of Kuniyoshi’s work but also contemporary ukiyo-e prints. The horimono tattoos were protection amulets for the firemen and other workers who risked their lives, fashion accessories, marks of courage, defiance and rebellion. Kyoukaku—vigilante gangs and, in part, precursors of the yakuza—were also known to wear these tattoos. Written records indicate formal gatherings of tattoo enthusiasts go back as early as 1830.

Meiji Era and the banning of the Horimono

After Commodore Perry knocked down Japan’s doors to the world in 1854, the Japanese government was focused on changing the country's image. Maybe because tattoos weren’t shown as overtly in the West or because they didn’t bolster a good reputation in those parts of the world either, the Japanese ruling class assumed they would be seen as barbaric relics by foreigners. Both irezumi and horimono were forbidden.

Gone were the markers of shame, but those of beauty and bravery were stubbornly kept alive in secrecy. The new tattoos were now hidden under clothes as they were in the West.

Even as a marginalized art, the 19th century saw many master tattooists practicing horimono and getting their due recognition even by, surprisingly, considering the reasoning for the prohibition, Western foreigners. One of these masters, Horiuno, worked mostly while the prohibition was still going strong and gained recognition throughout the country and even overseas. His customers were mainly construction and industry workers and, in 1920, some of these workers in the Kanda area formed the Kanda Choyukai, extending its membership outside the Kanda area to form the Edo Choyukai ten years later.

The group members were Horiuno customers, but also of his successors (Horiuno II and III), and they would meet frequently to show off each other's tattoos. Choyu-kai still lives on, and every year its members still gather at the Oyama Afuri on Mount Oyama to participate in ritual cleansing ceremonies, paying respect to the spiritual essence of the horimono art.

Post-War legalization and modernization

The prohibition was finally lifted under American occupation in 1948. And, once again, the American military barged open Japan’s doors to transform Japanese tattoo art.

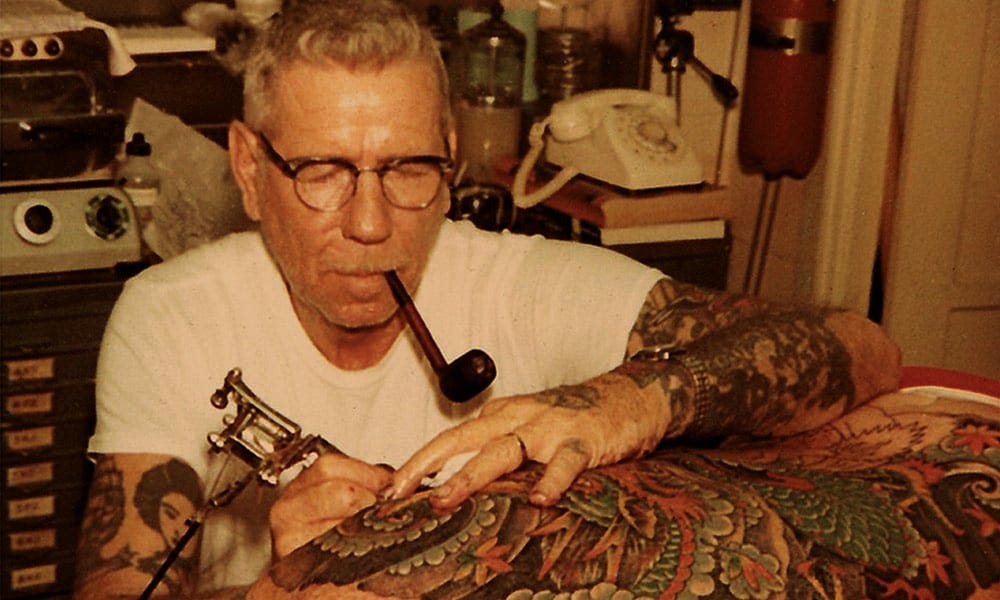

Horigoro I introduced the electric needle machine in Japan after meeting an American soldier who owned one. After noticing the colorful tattoos the American soldiers in Japan sported, Horihide traveled to Hawaii to meet the famous tattoo artist Sailor Jerry, and brought back new colors, safer pigments, and the mastery of the electric needle.

Even if the most traditional masters keep the old traditions, especially the use of the tebori, the doors were now open to the world. Horiyoshi III is an example of this by combining the horishi legacy with the knowledge he received from American artists, especially Ed Hardy, who motivated the Japanese master to learn even more about the Japanese culture behind horimono and influenced his decision to adopt the electric needle for outlines in his designs.

But not everything changed: tattoos were still largely more predominant among common people, both workers and criminals. With the dawn of the yakuza, there’s no doubt who some of the customers of these artists were.

🌺🍵 Special thanks to Catarina Periera who's been a stellar collaborator and a superb Ghostwriter. I'm very proud of the contributions she's made here and I admire the work ethic and grit that she demonstrated during the writing of this Mini-series.

✒️🐉 If you’re looking for exclusive content unpublished here on Substack, be sure to subscribe to my blog on Medium. It’s packed with a variety of pieces from reviews, social commentary, Poetry, health and Wellness, Nutrition , to Fiction Serials. Join the community and stay in the loop—consider subscribing. 🙂⬇️

https://medium.com/@chantlmcclary7/a-cultist-for-lajada-eed479ef9181